Chris Jaynes, the protagonist of Mat Johnson’s novel “Pym,” is a member of that particular species dubbed Loner-Academic. Spurned eons ago by a love named Angela, Jayne collects thousands of books, many of them rare, and into these dusty realms of paper and print, he retreats.

But Bard College, which appointed the self-described “Professional Negro” to teach African-American literature to privileged white kids, has cast him out. “Hired to be the angry black guy,” he wouldn’t serve on the school’s Diversity Committee. His logic: “It’s sort of like, if you had a fire, and instead of putting it out, you formed a fire committee.” Curing the country’s race ailments, Jaynes declares, “couldn’t be done with good intentions or presidential elections.”

Johnson nearly sends “Pym” into deeper race-in-higher-education hijinx, but then has his hero stumble upon an 1837 manuscript called The True and Interesting Narrative of Dirk Peters. Coloured Man. As Written by Himself. This pleases Jaynes, already shunned by his department for scholarly interests, which have drifted away from slave narratives and toward Edgar Allen Poe. Why Poe? To “understand whiteness, as a pathology and a mindset, you have to look at the source of its assumptions,” says Jaynes in one of the many slices of this book that reads more like lit crit than fiction. Poe “offered passage on a vessel bound for the primal American subconscious, the foundation on which all our visible systems and structures were built.”

Turns out Peters is a character from a real fictional work, “The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket,” Poe’s bizarre 1838 novel that recounts Pym and Peters’s nautical misadventures from Nantucket to Antarctica. After various travails, the duo discover an island, Tsalal, populated by black natives—what Jaynes calls “the great undiscovered African Diasporan homeland.” They leave the isle, and the book ends as they happen upon a giant figure looming among glaciers whose skin, Poe writes, “was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.” It was the era of theories about civilizations existing on islands, at the poles, or within a “hollow earth” accessible only at the poles, and though Poe later derided his enigmatic fiction as “a very silly book,’’ it influenced Melville’s “Moby-Dick” and inspired sequels by Jules Verne and H.P Lovecraft.

Poe also left behind some metafictional skullduggery: In the afterword to his novel, he claims the explorers survived and hired Poe to ghostwrite their tale. This trail of bread crumbs allows Mat Johnson to concoct an imaginary correspondence between Poe and Peters that Chris Jaynes tracks down. Believing Poe’s characters actually lived, Jaynes fantasizes about making “the greatest discovery in the brief history of American letters.” He eventually boards a ship bound for Antarctica, and the book shifts from tenure battles to battles with fantastic creatures. (In more snake-eating-its-tail chicanery, the preface states that Jaynes has hired Johnson to write his tale “under the guise of fiction.”)

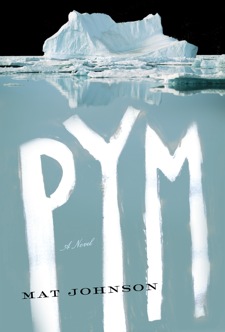

Genre-bending Johnson has used gritty traditions like the graphic novel (see his Incognegro and Dark Rain) and the thriller (Hunting in Harlem) to explore the underside of race and history. For Pym, he’s unearthed a Victorian adventure narrative aesthetic to recount a comic, race-tinged story of polar exploration.

The passengers headed south include childhood friend Garth, a man obsessed with Little Debbie snack cakes and the kitschy landscapes of a Thomas Kinkaid-like painter; a former civil rights activist with a scheme to sell Antarctic iceberg water; a gay, outdoorsy couple concerned with the intellectual rights to any discoveries; and, in the novel’s biggest stretch, old flame Angela (woefully flimsy as a character) plus her fresh husband. They run into that race of “super ice honkies,” the Tekelians, who enslave the all-black team in their subterranean ice city. “They all pretty much looked the same to me,” Jaynes winks to the reader in one of dozens of footnotes. Like his protagonist, the author is also a mulatto and once taught at Bard.

Pym is part throwback to the yarns of Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs, part exegesis of racial politics, part A.S. Byatt-style literary treasure hunt. It also wants a jab at “the fevered Caucasian dreams of Tolkien and Disney,” and in this quest, the prose invokes Stevie Wonder, Shirley Temple, Jim Crow, and Dungeons & Dragons. But Johnson’s culture-driven humor does not quite come fast or furious enough for Pym to fully succeed as social comment. The pulpy, ham-handed plot, ending in climactic violence, tries to carry the day, but exceeds the weight limit for which it was designed.

Yet as a kind of dreamscape, Pym oddly succeeds. What may lie at the frozen poles, be it subterranean labyrinths or lost species, has always fired the icy subconscious. Despite the grave visions of Orwell and Huxley, we still long for isolationist utopias, separate and not only not equal but better than the real.

The problem is when visions collide. “Here I was on the cusp of my own great dream, my own impossible truth,” Jaynes laments, arguing with his buddy Garth whether they should trudge across the ice to a cheesy painter’s domed Shangri-La or seek Poe’s black island paradise Tsalal—when both may not even exist—and “this gluttonous man was crowding it with his own improbable vision. There wasn’t enough magic in the universe for both of us.”

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms.